Composable Frontend Explained: How to Build a Future-Proof UI Architecture

Contents

Expand

TL;DR

- Composable Frontend (CF) is an architectural style that enables high flexibility.

- CF promotes building graphical user interfaces from small, independent and reusable building blocks, like Lego.

- CF is complex and expensive.

- Jamstack (Static-Site Generation, Atomic Deploys, Headless Data Providers) makes the foundation for CF.

- When integrating CF with Domain-Oriented Solutions (like Micro Frontends Architecture), better flexibility (and even higher complexity) becomes possible.

- There are ready-to-use CF solutions from the market that may help you get a quick start.

- CF is possible to implement from scratch and not use commercial solutions from the market.

Foreword

When talking about software architectures, we usually talk about backends. Due to various factors, including the contempt culture 1, we don’t talk often about frontend architectures. It led us to the common some time ago, no-frontend-architecture culture, which makes legacy projects interesting places to work at (see the “Kill It with Fire” book by Marianne Bellotti). 2

Fortunately, we started hearing about frontend architectures recently: Monolithic Frontend, Modular Monolithic Frontend 6, Micro Frontends 37, Composable Frontend, and others. This trend is a token of modern frontends complexity.

Composable Frontend is a contemporary approach to building highly flexible systems. There is a lot of hype around this concept today, and a regular technical guy may consider it as a new marketing campaign aimed at earning more money for corporations. From some perspective, this is true: think about the MACH Alliance, which big tech companies founded to promote their products. On another shore, there’s a Jamstack 5 whose main purpose is to promote architecture rather than specific products.

When googling “Composable Architecture”, there is a plethora of low-quality search results that are all about marketing. Preparing for this paper, I have reviewed tons of them — you can find some smirky comments about them in my X. I added some of them as references to this paper intentionally, as they may play a good role for understanding the market.

In software architecture, as in any other engineering discipline, marketing is not important by itself — an engineer must meet requirements by choosing matching technologies. Unfortunately, sometimes marketing does its job well and engineers manage to design poor solutions.

This post is not about commercial products. It is about the promising Composable Architecture that may be implemented in many ways. It demystifies misconceptions like “Commercetools has invented the Composable Architecture”, “Composable Architecture is only for e-commerce”, and others. It promotes critical and product-agnostic thinking in building software systems.

Software Engineer + Critical Thinking = Brilliant Solutions

Problem

Imagine a multidimensional frontend with many variables: color schemes, data sources, authentication providers, analytic tools, A/B testing vendors, payment platforms, and lots of others. It often happens in multi-regional applications, where different functionality is served for different markets.

Imagine the same multidimensional frontend with a requirement to reconfigure it in the runtime, w/o initiation of the code deployment. For instance, as a content manager, I want to have a way of configuring several versions of the home page for different regions and A/B experiments with no downtime and no deployment.

Sounds tricky. Right?

According to classical software design rules, IoC (Inversion of Control) is the best way of building highly flexible applications (see Martin Fowler writing about the Inversion of Control). 8 There is even a rule:

The later the dependency is resolved, the higher the flexibility is.

How to achieve this? How to resolve dependencies (UI components, their arrangement, and settings) on the fly, and distribute the updated frontend all over the world, not having the need of asking the development team to develop and deploy something?

Composable Architecture addresses these requirements. This article describes this in detail, based on my production experience.

Glossary

There is the following terminology around what the article is built on. Please, make sure that you are good with it, to make your journey as happy as possible.

- Composable Architecture 10 is an architectural style that promotes building software systems from small, independent, and reusable blocks, similar to Lego.

- Composable Frontend 14 is a particular case of the Composable Architecture, that promotes building frontends from small and independent bits of UI, similar to Lego.

- Micro Frontends 314 is an architectural style that is all about building frontends around business domains, that are independently developed and deployed. Similar to the Microservices Architecture.

- Jamstack 537 stands for JavaScript, APIs, and Markup. “It is an architectural approach that decouples the web experience layer from data and business logic, improving flexibility, scalability, performance, and maintainability”.

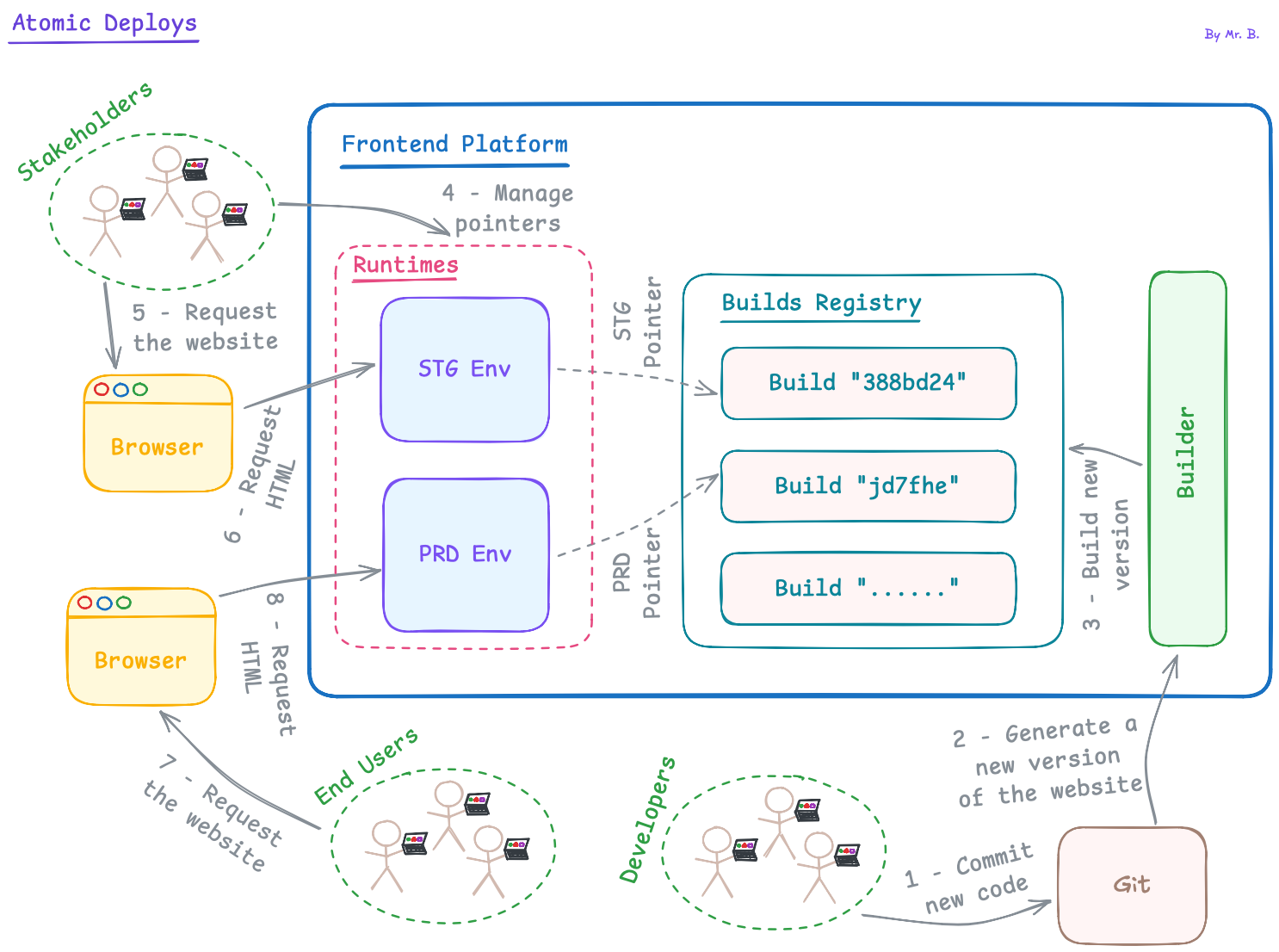

- Atomic Deploys 5 is a way of arranging zero-downtime releases by immutable builds, that are replaced in the runtime and not causing the maintenance period. Close to the blue-green deployment.

- Atomic Design 13 is an approach of building UIs from elements split by different levels: atoms, molecules, organisms, templates, and pages.

- Headless Software 17 is a kind of software that can operate without a GUI. E.g., for CMS, it is not required to present data in GUI.

- Headless UI 18 is an open-source library of accessible UI components that are free of specific styling, and may be used as a base for building a desired design system (DS).

- SSR 19 stands for Server-Side Rendering and means the rendering of a website’s HTML on a server rather than a client.

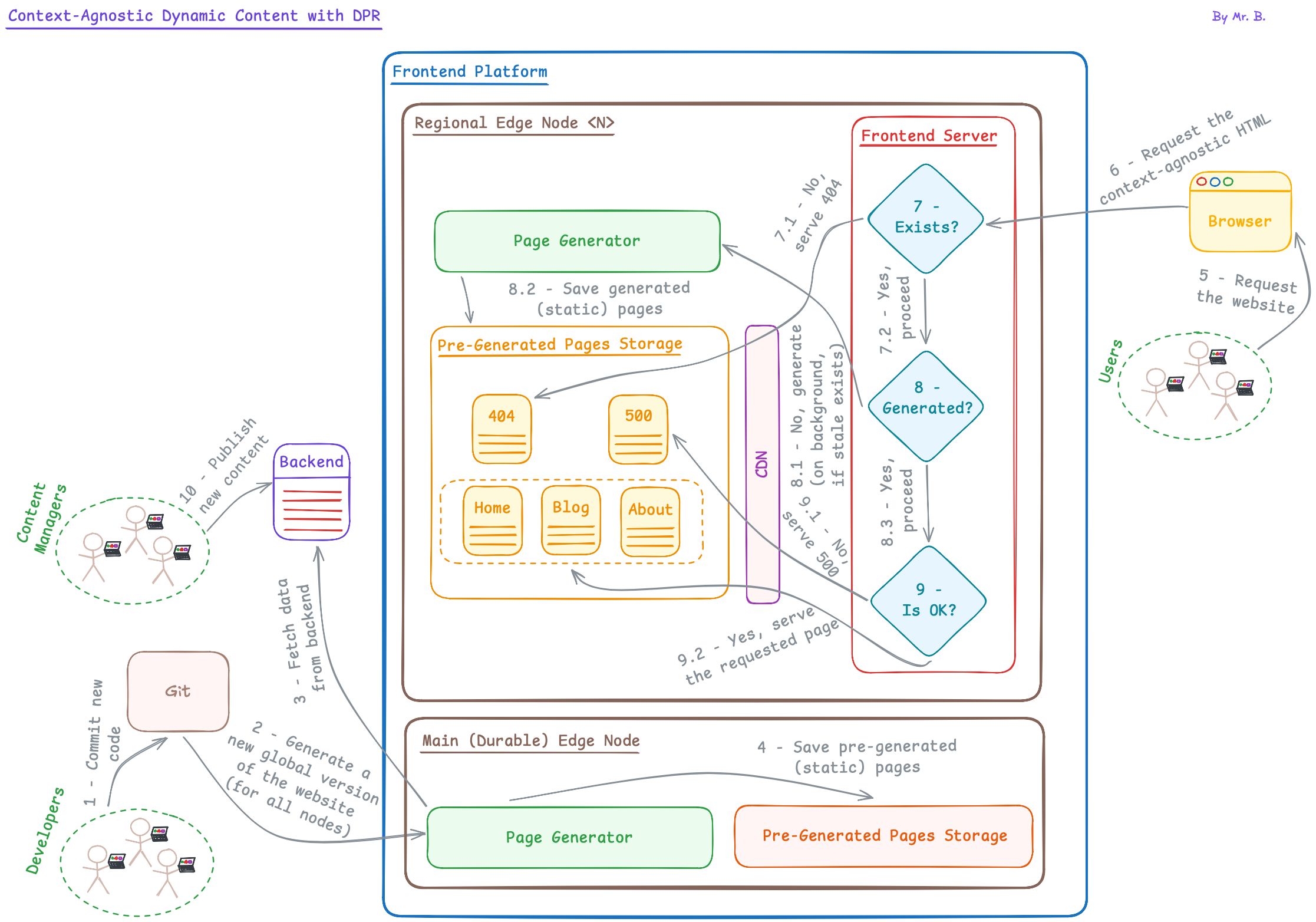

- DPR 20 stands for Distributed Persistent Rendering and means rendering web content on-demand (once it is requested) and spreading it in a geographically distributed manner. Invented by Netlify and based on Edge Networks.

- ISR 21 stands for Incremental Static Regeneration and means re-rendering static content with some time interval. It’s a killer-feature of Next.js. In combination with Netlify, it is based on CDN (unfortunately, not on the ODB and Edge Networks, at times when I was writing this article).

- MACH 9 stands for Microservices, API-First, Cloud-Native, and Headless. It forms an architectural style that is promoted by the MACH Alliance, that is a group of commercial products.

- Brick in this article means a reusable UI element that is isolated from other functionality. Nowadays, there is no universal term for this, and you may face different naming in different ready-to-use technical solutions (e.g., in Commercetools Frontend, the reusable and isolated UI element is called “tastic”). To avoid sticking to commercial products, I decided to invent a universal term pointing to the generic architectural approach. The term is based on the Lego example, that gives you enough flexibility to build literally anything from elements with a universal interface (i.e., bricks).

The Rise of Jamstack

Composable Frontend is a natural result of Jamstack.

The idea of decoupling UI from the backend is not new. However, we don’t often see this approach in practice (probably, because it is hard and expensive to implement). As building layered teams is not efficient, Jamstack and Composable Frontend get much more complex with domain-oriented organizational structures.

Anyway, Jamstack is at its peak of popularity due to how it solves one big technical problem — mixing frontend (presentation) and backend (business logic) codes, as we often see in PHP, Java, Python, and other programming languages that are common for the web development.

With Jamstack, the UI is a completely separate (decoupled) application, that is independently versioned, compiled, and deployed, and is made full of sense by filling with data coming from another application, responsible for business logic. Simply put, the UI gets a function of the (external, in terms of Jamstack) state. See this already classical article by Dave Rupert 22 for more details.

Composable Frontend is not possible without Jamstack.

The Power of Jamstack

Jamstack is quite a wide architectural style that suggests different techniques and tools for building scalable and extensible web applications. In its modern representation, it mainly promotes SSG (Static Site Generation), atomic deploys, headless data providers (like headless CMS), and domain-oriented solutions (like Microservices and Micro Fontends Architectures). Let’s review every of these techniques to gain more context about Composable Frontend and what it is built from.

Static Site Generation

It is fun to see that enterprises don’t believe this technique — they usually expect to see old good Server-Side Rendering (SSR) or Client-Side Rendering (CSR). Our mission is to communicate to clients the power of SSG, as its applications are underestimated.

Simply put, the SSG is all about generating the web page in advance (i.e., at the build time, when the application is compiled). It allows us to save time on generating the page once it is requested — a user receives the page generated beforehand. It opens a lot more opportunities, starting with good SEO (pages are fast and crawlable) and finishing with cost optimization of backends (the number of requests doesn’t grow with the traffic increase).

The main concern with SSG is related to the dynamic content. I.e., a statically-generated web page cannot be changed on its own when data change, and only the rebuild and republish can initiate the content update. With recent inventions, it is not a problem anymore.

There are two kinds of dynamic content:

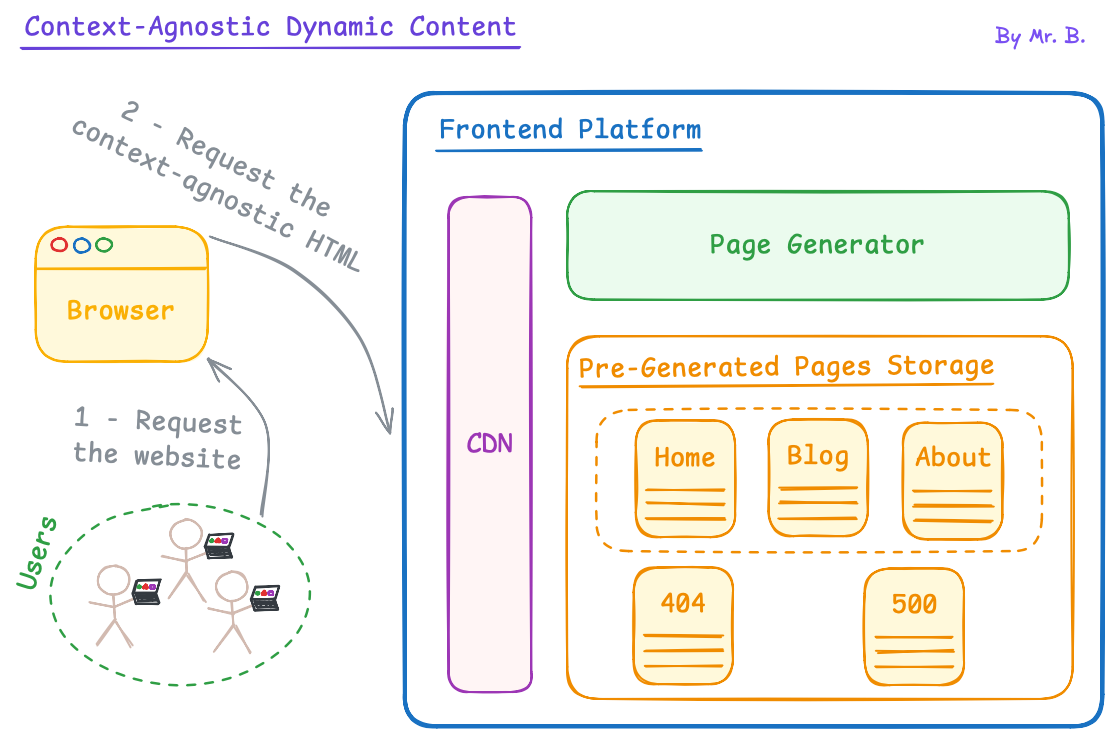

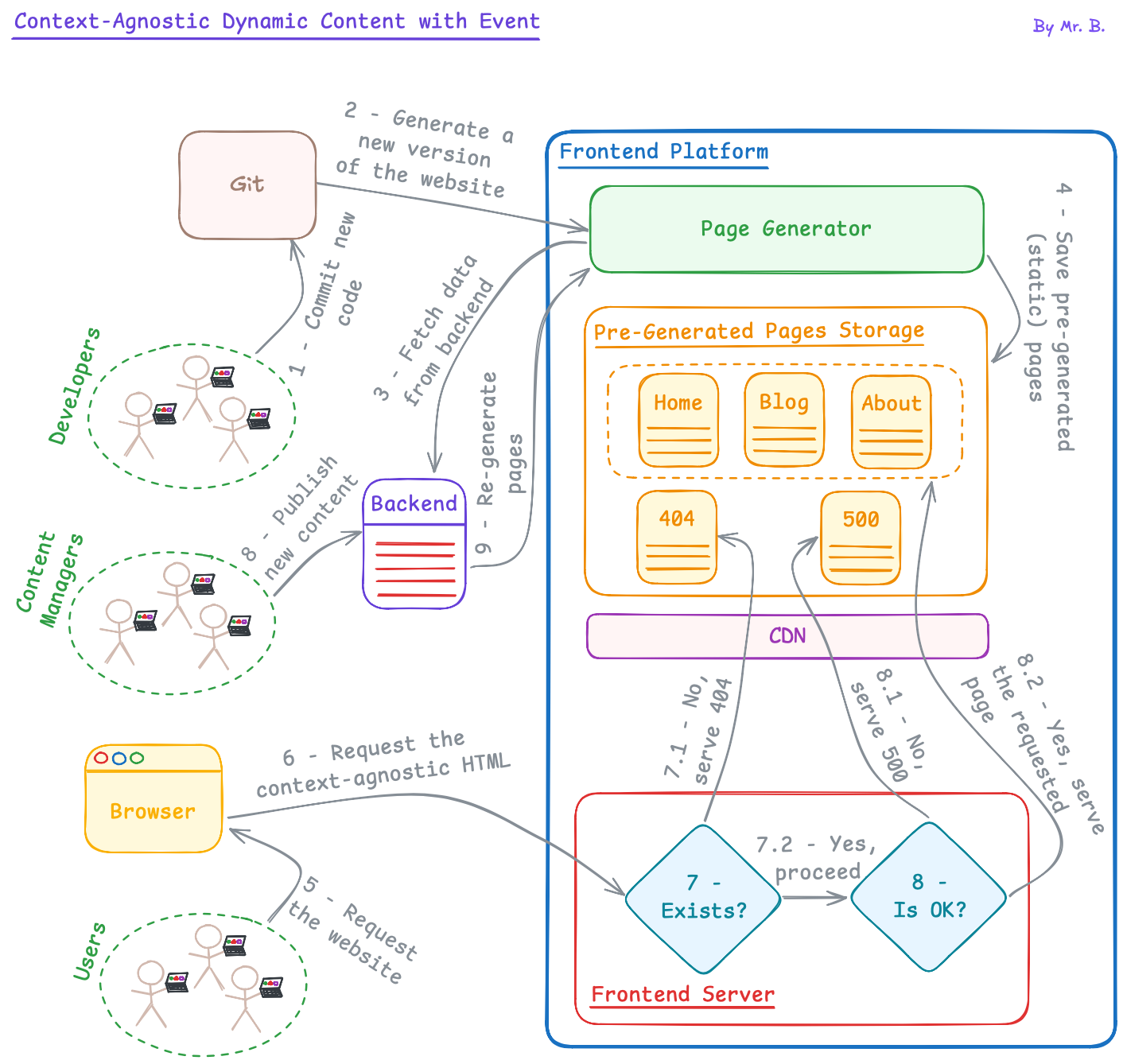

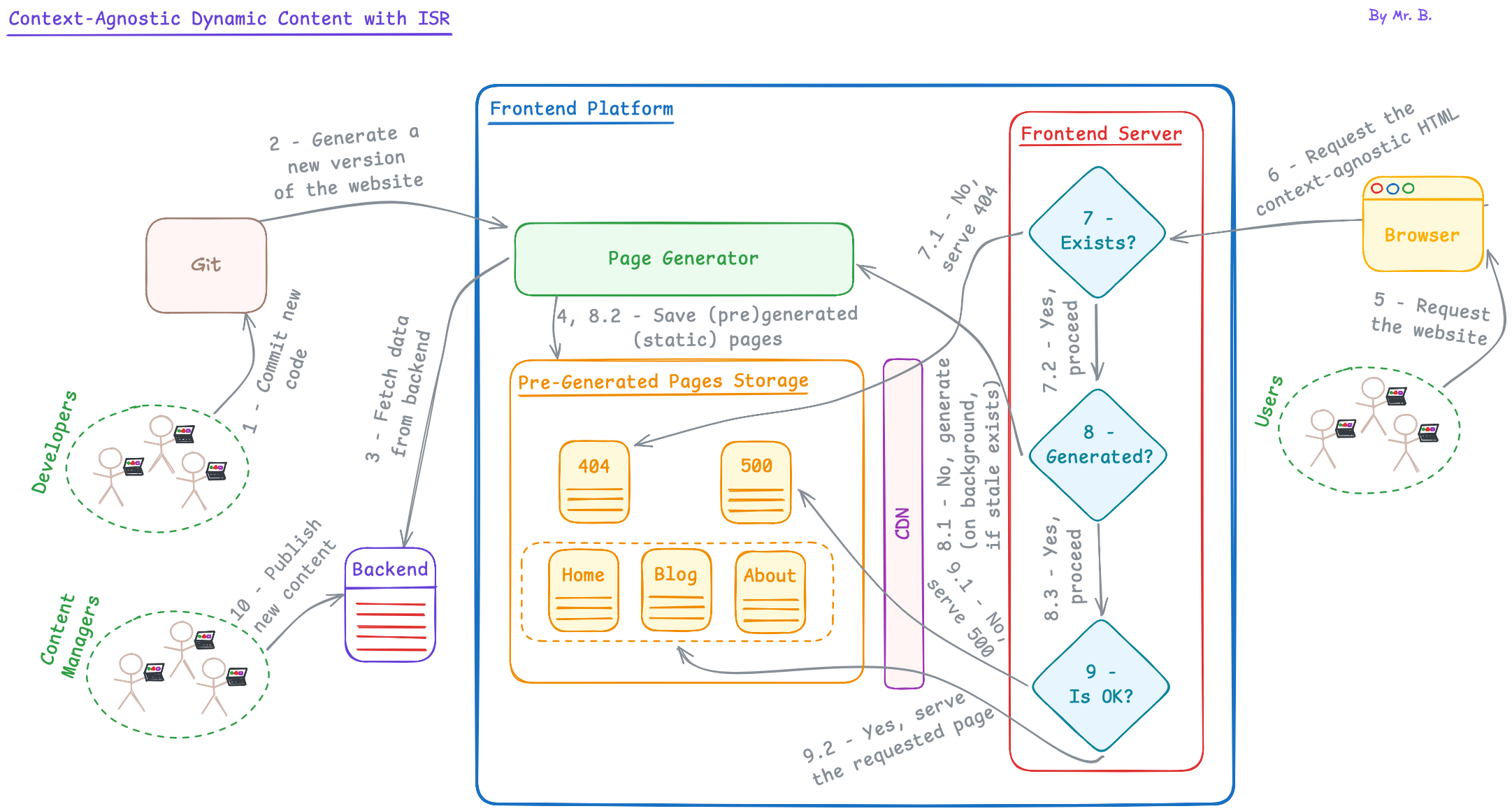

- Context-Agnostic Dynamic Content. This kind of dynamic content is based on the data from a backend and is the same for all the users (or a subset of users, e.g., within a specific location). For instance, it may be a header navigation coming from a headless CMS (content managers may want to extend it on the fly when creating new pages).

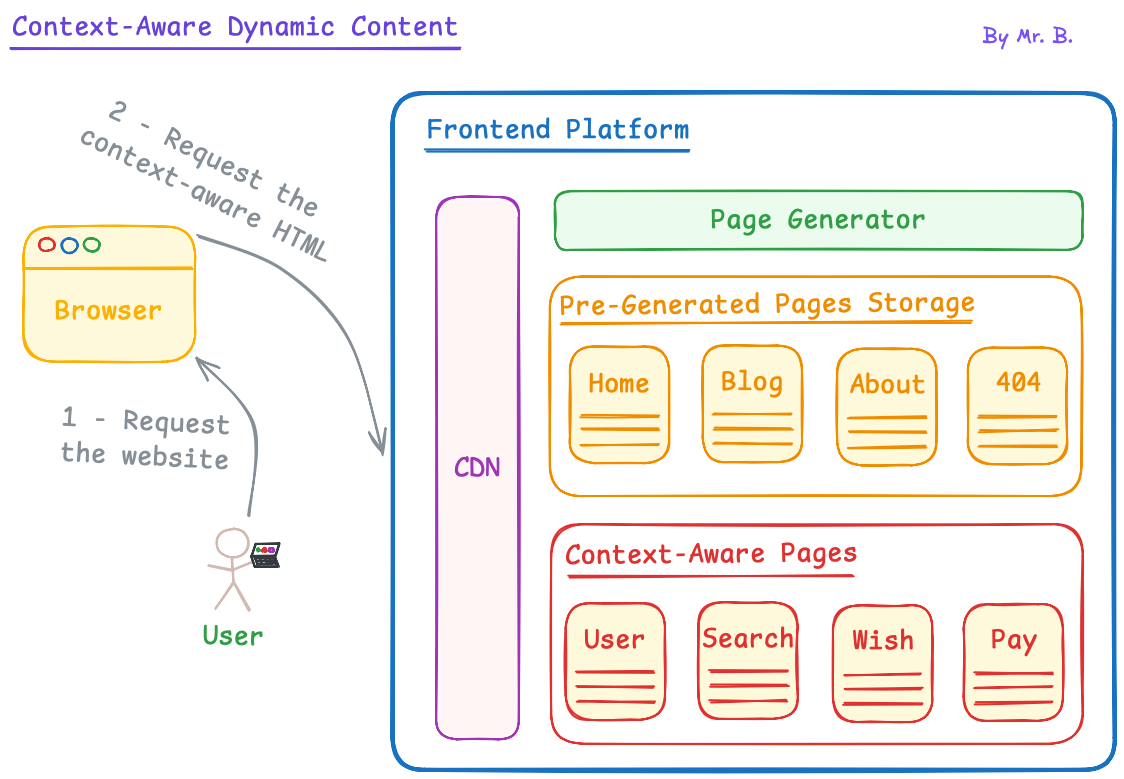

- Context-Aware Dynamic Content. This kind of dynamic content depends on the execution context. Usually, it is some information stored at the browser level like session/local storage, cookies, and so on. For instance, the context-aware dynamic content may be a user profile, a reading list, or a cart, which is based on the user’s JWT stored in cookies.

The context-agnostic dynamic content is not a big problem, compared to the context-aware one. There are the following solutions that address this problem:

- Event. When content changes, the event is fired to re-generate the website. It is a regular approach for static websites, which is easy to implement with modern CMS and frontend platforms due to ready-to-use API.

- ISR (Incremental Static Regeneration) is a feature of the Next.js framework. It allows to re-generate a static content with a defined time interval. The content generation happens on-demand (once a user requests the page).

- DPR (Distributed Persistent Rendering) is a general approach to building web pages on-demand and in a distributed manner. E.g., with the Netlify platform, the ODB (On-Demand Builders) implement the DPR, which allows to building a static content on-demand and invalidating it in a desired time interval. In modern frontend platforms, like Netlify, it is based on Edge Computing. ISR is very close to DPR, and from some perspective, it is valid to state that ISR implements DPR. However, there are limitations with ISR related to Edge Computing — usually, it is not available (on the day of writing this article).

The diagram below intentionally misses Edge Computing. As the ISR is a feature of Next.js, it puts some limitations on its implementation by service providers. Shortly, Vercel re-invented DPR in their manner, using the same SWR (Stale-While-Revalidate) caching strategy under the hood. To start with the topics, you can review this blog bost by Netlify 36, describing problems related to hosting Next.js on anything that is not Vercel. Probably, when you read my article, the problem has already been solved, and Next.js has become more open to the community.

Desirably, the ISR must use Edge Computing on all the platforms.

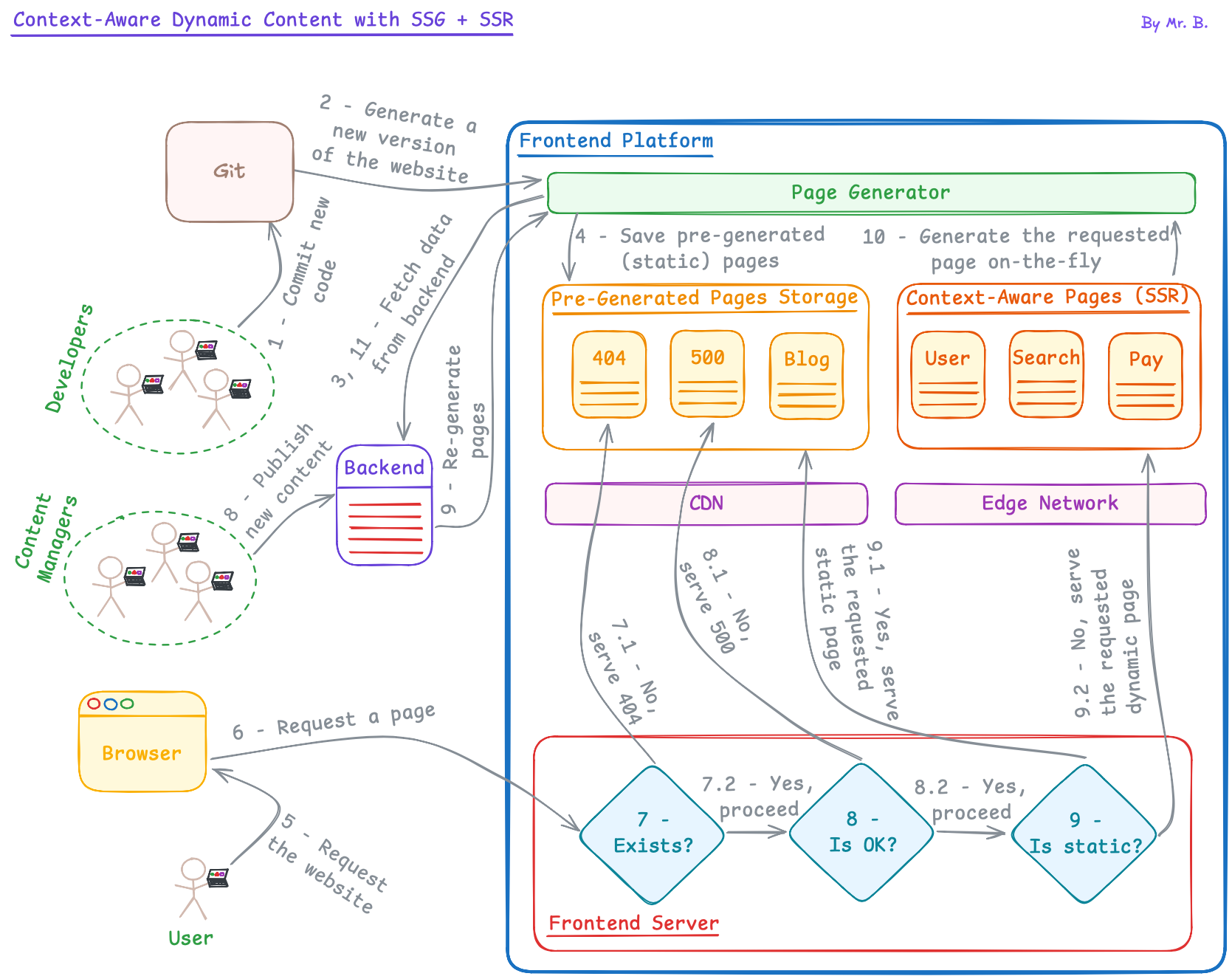

The context-aware dynamic content is a tricky thing. My recommendation is to consider the context-aware dynamic content as a no-go case for the SSG. The main reason is that it makes no sense to generate a static page for a single user — there are no benefits from both performance and financial perspectives. There are the following options that may be considered in this case:

- SSR (Server-Side Rendering) is a general approach to rendering web pages on a server in a dedicated manner for every request. For some old monolithic-oriented architectural patterns like MVC that were built around PHP, Python, and Java, it was a common thing. For this reason, SSR is sometimes mixed with those messy architectures, and discarded due to bad reputation as a result. However, SSR is a separate thing from the monolithic stuff, and may be successfully used for Composable Frontends with headless data providers. In many cases, SSR and SSG go together: context-aware pages are served with SSR, and content-agnostic ones with SSG.

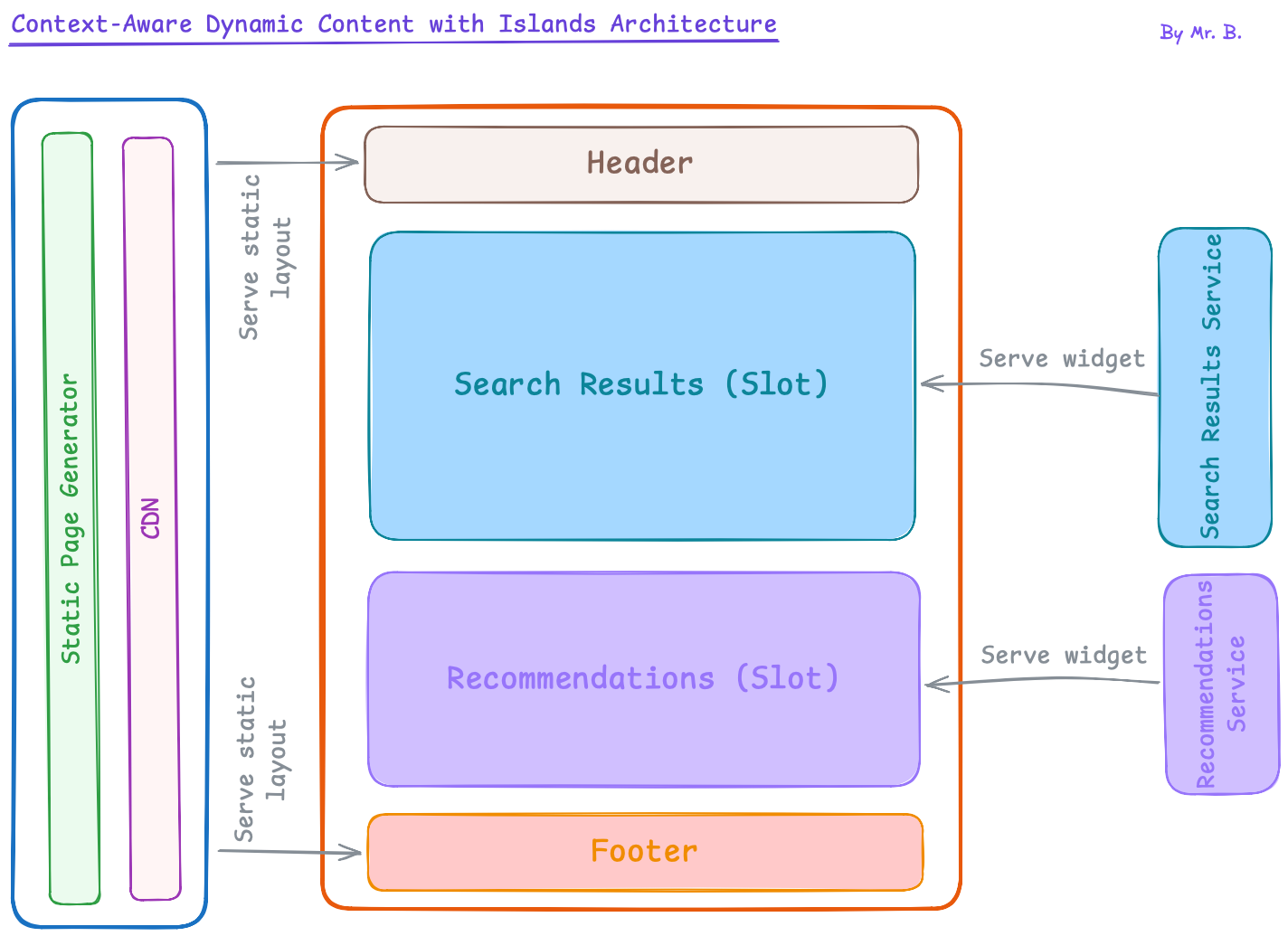

- Islands Architecture 23 is a general idea of rendering static and dynamic elements of web pages separately and independently. It is a very fresh idea that lies in a foundation of cutting-edge and exotic frameworks like Astro 24 and Tropical 25. If you start a new project, or Micro Frontends are in place, it may be an option for you to pre-render static or context-agnostic dynamic content on a server and render context-aware dynamic content (widgets) on the client. Conceptually, it aligns well with the Composable Frontend.

Atomic Deploys

This is a Jamstack approach to managing zero-downtime deploys. As the term suggests, deploys are arranged with deployable atoms — stateless, immutable, and self-contained artifacts. Self-contained means that every deployable atom contains everything required for the service runtime: code, assets, configurations, and even pipelines (e.g., for GitHub Actions).

Atomic deploys are based on the Artifact-Based Deployment concept. 27 The main idea is to have a registry of self-contained deliverables that may be easily switched in different environments with no downtime. In my experience, it works well with Trunk Based Development. 28

Atomic deploys are an integral part of the Composable Frontend Architecture. They allow quick experiments and short feedback cycles with minimal risks, allowing you to quickly revert the code that doesn’t work expectedly. At the same time, they make Micro Frontends and independent deployments more manageable.

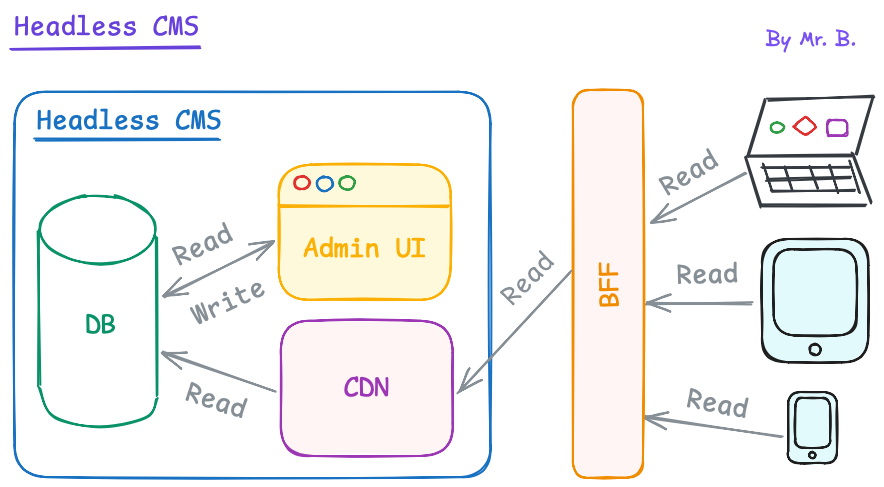

Headless Data Providers

Headless architecture has become a buzzword. This is one more concept that is overused by recently emerged commercial organizations to make their products sellable. However, the concept of headless data providers is not new — it is something that we can learn from classical resources about computer programming.

As the term implies, “headless” means that something misses its head/face — i.e., it misses its view/presentation. In terms of data providers, it means that “headless data provider” does not have a graphical user interface — it’s responsible only for managing its data, and is not concerned about how they are presented to end users (it’s a responsibility of some other service, that we are not interested in at this level). This is how the term “Headless CMS” emerged, meaning that the content is separated from how it is rendered to end users.

As we have already seen before, this concept was also broken by popular some time ago architectural patterns like MVC. The main benefit of such patterns is in their simplicity, and in some cases, they may still be suitable. However, within the Composable Frontend Architecture, it makes sense to consider mixing data and its presentation in a single application like in MVC an anti-pattern — it contradicts the Jamstack principles at least.

It’s hard to imagine a Composable Frontend without headless data providers. They provide several benefits that make them a good choice:

- Business domains separation (content management and data presentation). Good for the independent and parallel work of different organizational departments responsible for content and graphical user interfaces.

- Services separation (content providers and content consumers). Having independent services for different purposes makes a system more reliable (e.g., downtime of some content consumer does not affect the content provider) and secure (e.g., in a Zero-Trust Architecture 29, every service is protected which makes the whole system more secure).

- Headless data providers may be consumed by different consumers. E.g., in an enterprise-level application, for the same data provider there may be several consumers with different purposes — data presentation, data transformation, and so on.

The Power of Composable Frontend

The Composable Frontend brings your team the power of building new features from reusable software bricks, like you do with Lego.

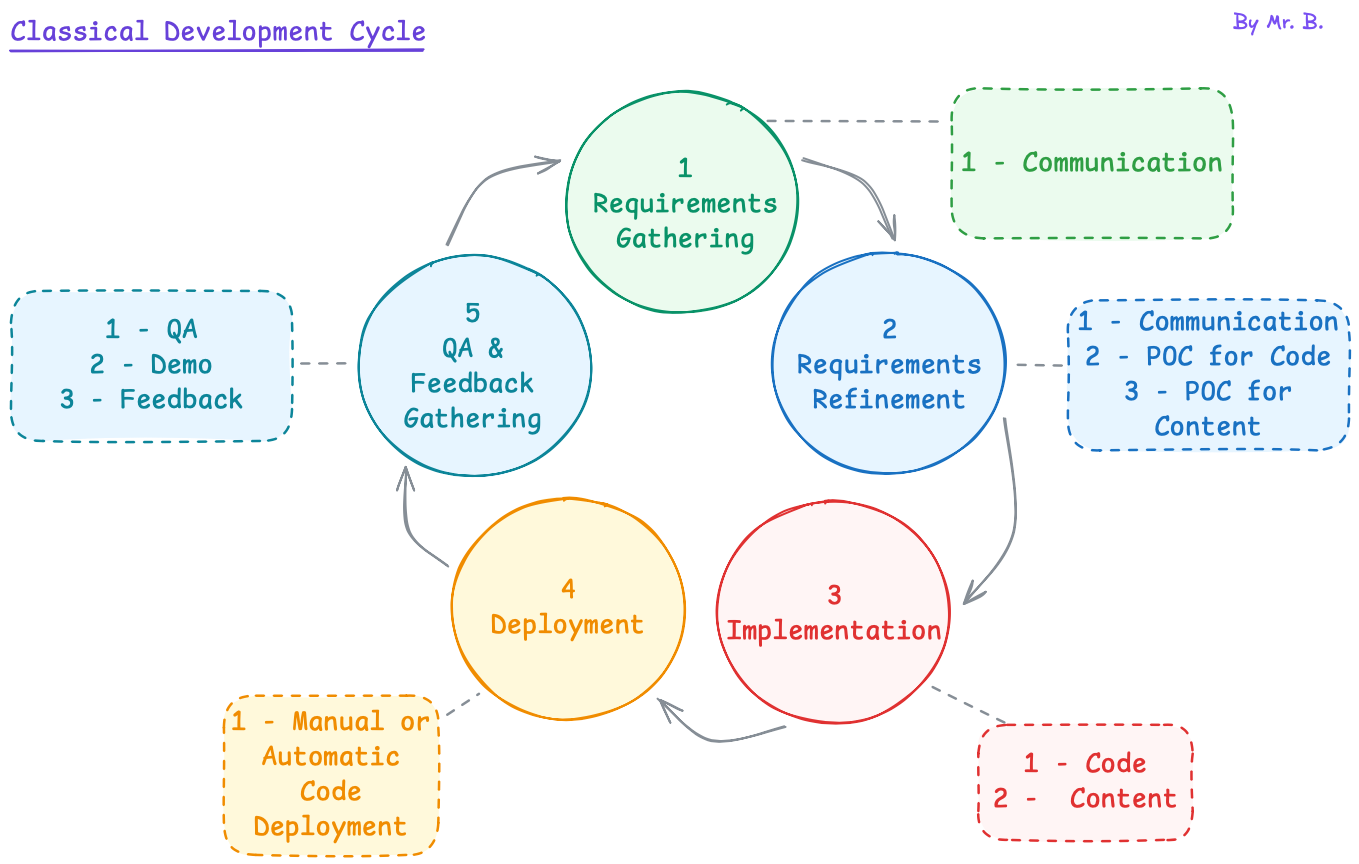

In a classical software development, when there is a new feature request, there is the following simplified loop that teams usually step into:

- Requirements Gathering. At this step, you work with a feature requester closely to gather as much information as possible to understand what must be implemented.

- Requirements Refinement. The request must be verified with the technical team. As the technical team knows the system well from the code perspective, they may imagine how the new feature may be implemented, what is required for the implementation, and how much it may cost. During this step, you can recognize technical blockers, that must be communicated to the feature requester back. You may want to arrange POC at this stage to verify the hypothesis and return to the first step in case of failure.

- Implementation. The technical team does a magic with the code to make the feature request a reality. Some code is reused, some new code is implemented from scratch. Probably, during the implementation, the team may decide to use some open-source libraries.

- Deployment. Once the code is ready, it is time to deploy it to make visible to stakeholders. Once it happens, everyone with an access can review the new feature.

- QA and Feedback Gathering. Once the code is deployed, it is time to test the implementation and gather feedback from the team. The feature demo makes sense at this stage. It may initiate a new loop of the development cycle to improve the feature.

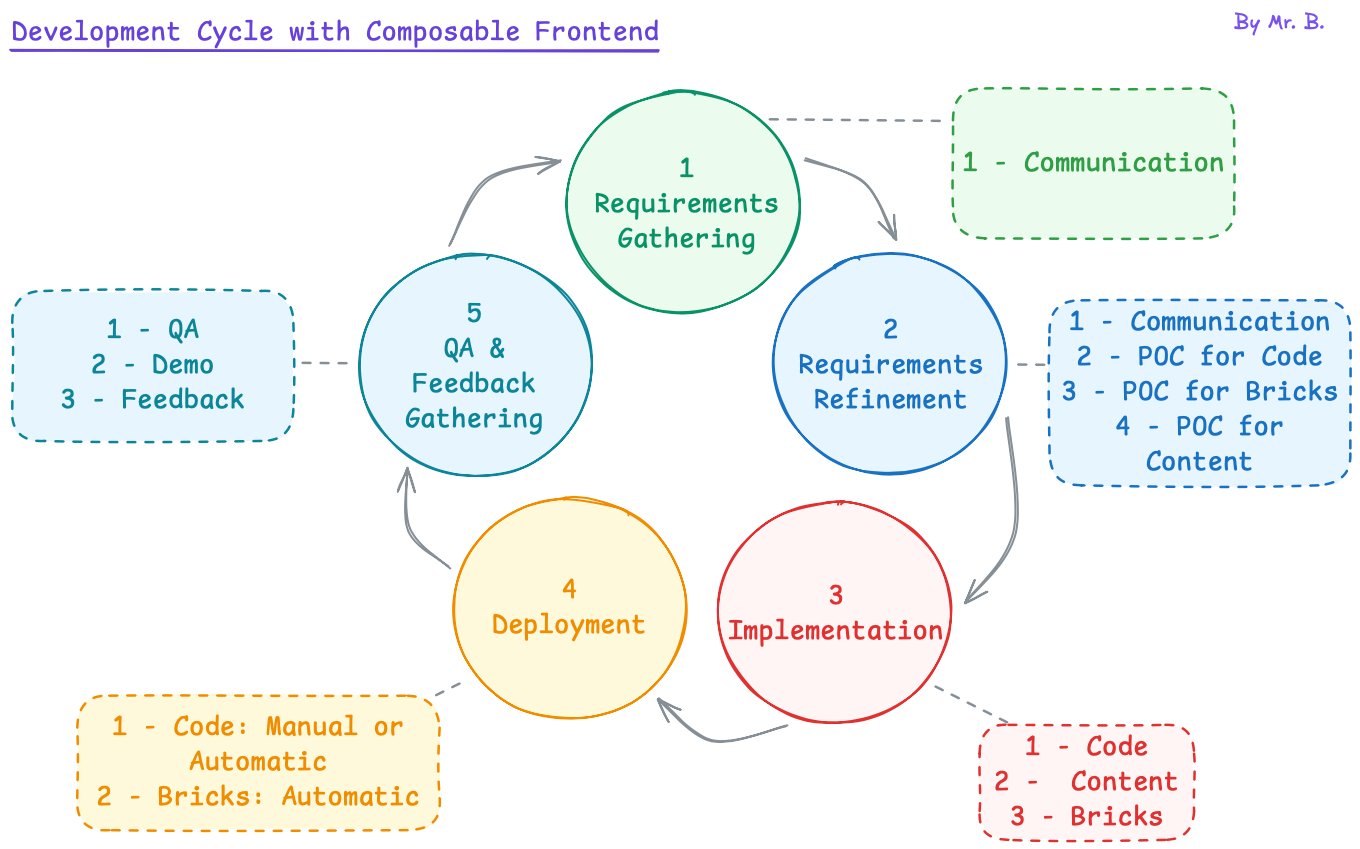

As you can see, with the classical approach, the new feature development (e.g., introducing a new web page) is mostly about working with the code. With the Composable Frontend Architecture, the development cycle looks a bit different, shifting the step about new code creation towards content management:

- Requirements Gathering. Nothing special, everything stays as it was.

- Requirements Refinement. The difference starts from how the technical team thinks about the new feature implementation. With the classical approach, a technical person may first think about how he/she can reuse the existing code/module, and then decide on what new code (probably, a new module) must be introduced to satisfy the requirements. With the Composable Frontend, the technical person starts thinking about the new feature in terms of reusable UI components (i.e., “bricks” or “building blocks”) that can be put together to satisfy the requirements; and only after that it may require thinking about what new “bricks” must be introduced, and what code development is required for that. You may want to arrange POC at this stage to verify the hypothesis and return to the first step in case of failure; the Composable Frontend may simplify the POC due to the possibility of runtime experiments.

- Implementation. With the Composable Frontend, the implementation doesn’t always mean that you must write a new code and deploy it somewhere. In some cases, you may reuse already existing bricks, and the feature request can be addressed with configuration activities. E.g., if the request is about introducing a new page, that is based on the already implemented design system (consisting of atoms and molecules, i.e., bricks), you can combine these bricks in a proper way to make the new page work as requested.

- Deployment. The difference is in how the feature is implemented. If it requires development on the code level, there are no significant differences. However, if the feature is implemented from already existing bricks, the deployment happens automatically because of properly implemented CI/CD pipelines. Once it happens, everyone with an access can review the new feature.

- QA and Feedback Gathering. Nothing special, everything stays as it was.

Definitely, it’s a simplified model. As the Composable Frontend is more complex by its nature than the classical development style based on the coding, it introduces some overhead around DevOps: bricks must be developed and tested independently, it leads to more complex deployments, and is multiplied by the need for automatic releases and on-demand cache invalidation. (However, if you base your system on a platform like Commercetools Frontend, the complexity of deployments may be hidden from you.)

The more flexibility you want, the more complexity it brings.

| Development Cycle Step | Classical Development Cycle | Development Cycle with Composable Frontend |

|---|---|---|

| Requirements Gathering | Communication | Communication |

| Requirements Refinement | Communication POC for Code POC for Content | Communication POC for Code POC for Bricks POC for Content |

| Implementation | Code Content | Code Content Bricks |

| Deployment | Manual or Automatic Code Deployment | Manual or Automatic Code Deployment Automatic Bricks Deployment |

| QA and Feedback Gathering | QA Demo Feedback | QA Demo Feedback |

The Power of Domain-Oriented Teams

The Composable Frontend enables domain-oriented teams. In my opinion, it looks like one more architectural enabler for DDD in the frontend world, alongside Micro Frontends. Like with Micro Frontends, which allows you to split teams by business features, the Composable Architecture allows you to split teams by reusable building blocks (bricks).

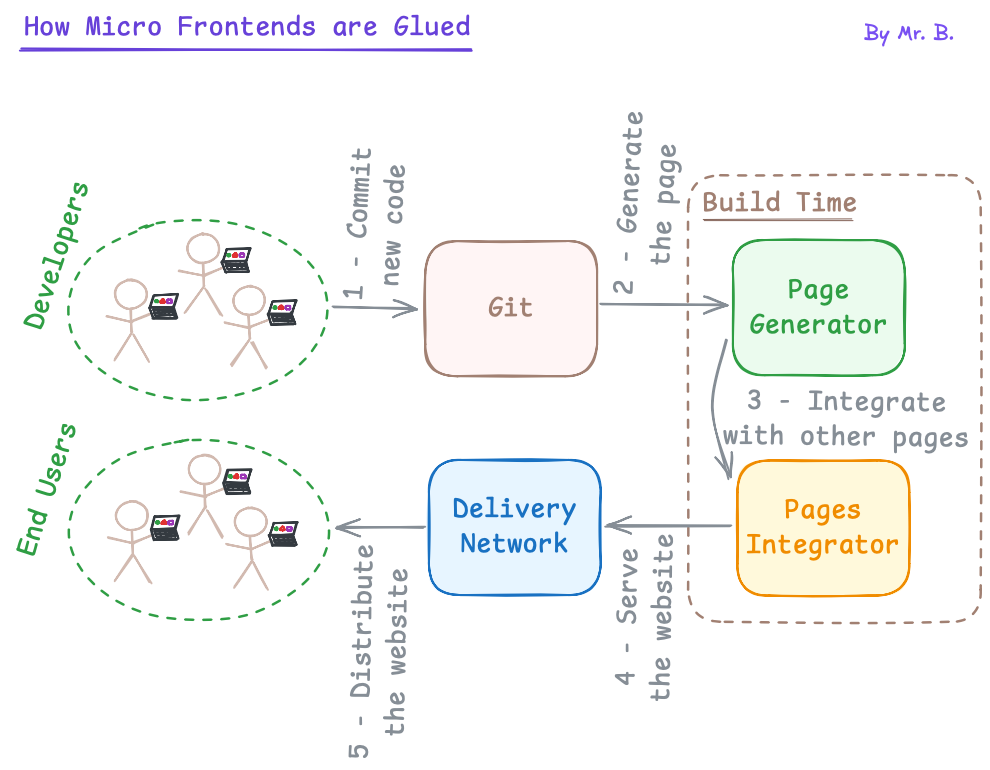

Comparing to Micro Frontends, the granularity of isolated UI elements in the Composable Frontend is higher. With Micro Frontends, a domain-oriented team may own an end-to-end business feature that is already glued into a seamless application (considering the generic architecture, in some Micro Frontends implementations, such features may have dedicated URLs).

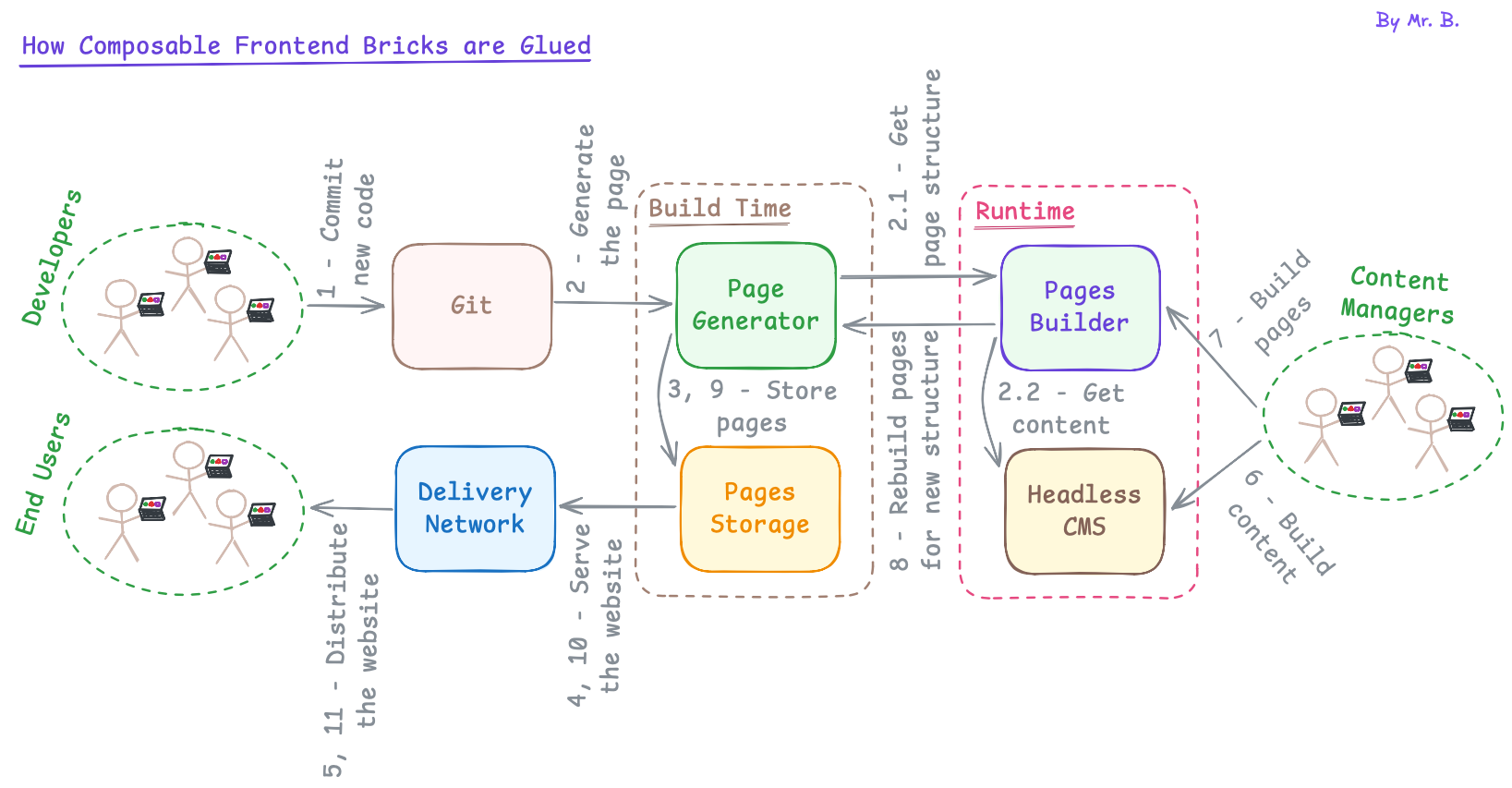

With the Composable Frontend, a domain-oriented team owns a set of bricks that still must be glued together in the runtime (the foundation for this is the pages/features configuration/structure that may be exposed to business actors like content managers). I.e., Micro Frontends are usually glued into an application during the build time, and composable bricks are glued in the runtime.

Both Micro Frontends and Composable Frontend (that is based on Composable Architecture) are architectural styles. They don’t conflict and may be used together. E.g., the corporation may own a number of micro frontends implemented independently and with different approaches: classical monolithic web applications, modular frontends, composable frontends, static landing pages, and so on. This mixed nature is fine for Micro Frontends Architecture, and it doesn’t block us from integrating all of these sub-systems into a single and seamless one.

With Micro Frontends, you can mix UI frameworks (like, Next.js for a Blog, and Angular for an Admin Room). The same blending is not easily possible with the Composable Frontend unless different Composable Frontends are arranged as different Micro Frontends and compiled independently.

The Micro Frontends Architecture is a separate topic, and Micro Frontends and Composable Frontend Architectures 14 is a good resource for diving deeper into this topic.

It is worth noting that the full potential of bricks may be implemented only with the maximum level of isolation (same as with Microservices).

The more isolation of bricks you support, the less your domain-oriented teams interrupt each other.

In reality, the full isolation is never possible. Probably, you will want to share the following things, dedicating them to appropriate teams (or the Core Team, which is responsible for the global functionality that glues bricks together to make an organism from organs):

- Design System (DS). It is a set of core (kit) UI components usually represented as Atoms (in terms of the Atomic Design 13). It makes no sense to support several Design Systems, incapsulated inside domain-oriented teams. In some cases, the Design System may be taken from the web: Material UI, Ant Design, and others. The corner case is when different business features depend on different Design Systems.

- BFF (Backend for Frontend). It makes sense to have a single entry point into backends for all the bricks and domain-oriented teams. It differentiates the Composable Frontend from Microservices, which depend on data storage isolation heavily. However, you are not limited technically and may achieve the data isolation for domain-oriented teams, but not for bricks. For instance, you may want to support BFFs dedicated to domains.

The Complexity of Putting Everything Together

There are a lot of complex topics under the hood of the Composable Frontend. Putting everything together leads to the steep learning curve for technical and business teams. As with exotic programming languages like Rust, you will struggle hiring engineers from the market ready-to-go with the Composable Frontend. It looks more sensible to gradually teach your teams and learn from your mistakes. (Like we do on projects I participate in.)

To mitigate the complexity of the Composable Frontend, you may consider following some of the suggested below techniques. They may look obvious from the first approach, but they are full of pain for teams that have coined them on their production experience:

- Divide & Conquer. The Composable Frontend is possible to be hidden from regular engineers. I.e., when a junior frontend developer implements a Product Gallery UI component, the Composable Frontend must not concern her/him. The integration of bricks may be dedicated to a separate team/member responsible for the “composability” of the frontend.

- Modularization. It’s so hard to implement the “Divide & Conquer” model when module boundaries are not clearly defined. It is a regular problem for monolithic codebases where engineers can import everything from everywhere into their pieces of code and merge such a code successfully without a thorough code review. The best option to fight with this problem is DDD and modularization: when modules are hardly separated from each other, the team has no more options rather than supporting the desired separation of things. (In my experience, a monorepository was always a good decision to split things with minimal overhead.) Also, you can consider implementing something like a Feature-Sliced Design 32.

- Evolution vs Revolution. The world is not ideal, and there are no ideal solutions. Try to arrange the evolutionary culture and never try to introduce ideal solutions. For instance, don’t hurry up decomposing a monolith into modules: firstly, outline the module boundaries; secondly, spend some time with a virtual module kept as a part of a monolith, and only then arrange it as a separate module. Doing the same in the revolutionary mode, you may introduce problems for engineering teams, banging them with breaking improvements.

Composable Frontend in Action

There are two primary options if you strongly decided to go with the Composable Frontend Architecture:

- Implement the composability feature on your own. Probably, based on open-source libraries.

- Choose a solution from the market.

Both options are good, and the decision depends on various variables. These are some of them:

- Self-Grown Composable Frontend:

- The project is long-term.

- You want to fully control your system.

- Your engineering team is strong.

- You have enough software development budget.

- Outsourced Composable Frontend:

- The project is either short- or long-term.

- You are good with delegating the frontend composability feature implementation to a vendor.

- You are ready to have endless communications with the Composable Frontend vendor about problems and desired features.

- You have enough budget on vendors.

What is wrong with the Composable Frontend? From the points above someone may think that it is broken by architecture.

But it is not.

This is the summary about the Composable Frontend from the points above:

- Expensive. In both cases, this architecture costs much. Primarily, it is caused by its complexity.

- Complex. In both cases, the architecture is complex. But the kind of complexity may change, depending on the choice.

- Long-Term. This architecture looks profitable for large, prospective and long-term projects. In case of short ones, it will probably cause only losses. However, this point is ambiguous, and may be wrong in some unique cases (like a flexible marketing page for an offline shop managed with no code changes).

Be careful with your requirements and make decisions thoughtfully.

Composable Frontend Solutions from the Market

It is not a marketing article. I.e., I don’t promote commercial solutions — only general concepts are in the scope. However, the article would not be full without mentioning big players in the Composable Frontend World just for the general information.

In my production experience, I faced the following Composable Frontend platforms. Probably, when you read this paper, something has already changed.

- Netlify Create

- Commercetools Frontend

- Elastic Path

- And others…

Self-Grown Composable Frontend

It is possible. However, it is not easy.

In the next part of the Composable Frontend series, we will talk about the main principles that will allow you to start building your own solution.

Summary

Composable Frontend is an architectural style that promotes building graphical user interfaces from small and reusable building blocks, like Lego.

This architecture is complex to implement and support, as it requires advanced skills in the following fields: software development, solution architecture, DevOps, content management, system documents, and many others. I.e., you have to be ready to manage a technically entangled software system.

On the other hand, the Composable Frontend (and the Composable Architecture in general) brings a number of benefits: the system becomes highly flexible and manageable. The flexibility costs, and you are welcome to pay for it in case it brings revenue.

There are ready-to-go solutions from the market, that allow to start with the Composable Frontend quickly. However, if you need something unique, you can implement this architecture yourself, growing your own Composable Frontend Engine.

The Composable Frontend Architecture is built upon the Jamstack Architecture, which promotes cutting-edge techniques like Static-Site Generation, Atomic Deploys, and Headless Data Providers. When integrating it with Domain-Oriented Solutions (which is possible with Micro Frontends Architecture), you can achieve even more flexibility and parallel development in enterprises.

The Composable Frontend Architecture is a strong thing that enables high flexibility. However, it costs.

References

- Contempt Culture - Article by Aurynn Shaw

- Kill It with Fire: Manage Aging Computer Systems (And Future Proof Modern Ones) - Book by Marianne Bellotti on Amazon

- Micro Frontends

- Frontend Architecture for Design Systems: A Modern Blueprint for Scalable and Sustainable Websites - Book by Micah Godbolt on Amazon

- Jamstack

- Deconstructing the Monolith: Designing the Software that Maximizes Developer Productivity - Article by Kirsten Westeinde from Shopify about Modular Monolith

- Micro Frontends in Action - Book by Michael Geers on Amazon

- Inversion of Control Containers and the Dependency Injection Pattern - Article by Martin Fowler

- MACH Alliance

- Guide to Composable Architecture - Article on Netlify

- A Beginner’s Guide to Composable Architecture - Article on Netlify

- Composable Architecture - Blog Posts by Netlify

- Atomic Design - Book by Brad Frost

- Micro Frontends and Composable Frontends Architectures - Handbook by Natalia Venditto

- Micro Frontends - Article by Cam Jackson

- Building Micro Frontends: Scaling Teams and Projects, Empowering Developers - Book by Luka Mezzalira on Amazon

- Headless Software - Wikipedia

- Headless UI - Library of Accessible and Unstyled UI Components

- Rendering - Documentation by Next.js

- Distributed Persistent Rendering: A new Jamstack approach for faster builds - Article on Netlify

- Incremental Static Regeneration (ISR) - Next.js Docs

- UI=f(states^n) - Article by Dave Rupert

- Islands Architecture - Article on patterns.dev

- Astro Framework

- Tropical Framework

- Next.js Framework

- The Immutable Revolution: Embracing Artifact-Based Deployment Models - Article on LinkedIn by Robert J.

- Trunk Based Development

- Zero Trust Architecture - Wikipedia

- Semantic Versioning

- Keep a Changelog

- Feature-Sliced Design - GitHib

- Enhance your Composable Frontend Architecture with Micro-Frontends - Commercial Article on Mia Platform

- Composable Frontend Architecture for 2024 - Medium

- What is Composable Architecture? - Commercial Article on Alokai

- How we run Next.js today — and what should change - Article on Netlify

- WTF is the Jamstack? A goofy name for a great web architecture. - Article on Code TV